Interview with Martin Fischer, Consartis

What a passenger plane has in common with a pot of yogurt

As a former Airbus and military jet pilot, Martin Fischer worked for many years in security-critical environments. Today, he contributes his knowledge and experience as a business mediator, management consultant and negotiation expert in various industries. He is the owner of Consartis and ich-suche-rat.ch.

Martin Fischer spent many years flying passenger aircraft and military jets. Today, he advises companies on safety matters. At Food Day on 10 April 2025, he spoke about safety culture from a pilot’s perspective. In this interview with SQS, he shares how an open approach to error can open up new opportunities, the role of ISO 9001:2015 in quality management—and how a gut feeling once saved his life.

Mr Fischer, as a former Swissair and military jet pilot, you have countless hours of flying behind you - is there a safety rule from the cockpit that you also take to heart in everyday life?

Absolutely. One of my favorite principles is what's known as "shared situational awareness". In other words, constant awareness of the current situation. As a pilot, I always have to know where I am, where I’m going, and what might affect safety. Applied to everyday life, this means recognising risks at an early stage and acting accordingly - for example in company management or quality control. But I also often apply the "Aviate, Navigate, Communicate" principle. It means: first fly steadily, then choose the right direction, and finally communicate. This prioritisation not only helps me in the cockpit, but also when making critical decisions - be it business or private.

On 10 April, you were a guest speaker at Food Day 2025. What does flying have in common with yogurt production?

Quite a lot. Both the aviation and food industries work with strict safety standards, as errors can have serious consequences - be it an air accident or a product that is harmful to health. Both industries therefore rely on precise processes, clear responsibilities, and multi-level controls to identify and eliminate risks at an early stage. A strong safety culture is crucial in this context.

What is a stable safety culture?

It goes beyond merely complying with regulations—it's a mindset that’s embraced throughout the entire organisation. It means, for example, that all employees are aware of the risks of their work and act responsibly. Safety is therefore not a task for individual departments, but a shared obligation. The willingness to learn also plays a central role. Companies that not only analyse errors, but also understand and develop their successful processes, create a stable safety culture in the long term. This culture is based on trust and promotes an environment in which concerns can be expressed openly.

So, dealing openly with mistakes plays an important role?

In any case. A genuine safety culture requires a change: away from the blame game with its finger-pointing and towards the "just culture" principle with its open error culture. In aviation, we have accepted that mistakes are unavoidable - regardless of experience or training. Instead of looking for someone to blame, we therefore create an environment in which errors are recognised, understood and used to create systems that recognise and correct them at an early stage. In the cockpit, we therefore work according to the principle "We focus on the "what" and "why"—not the "who"". This fosters transparency and helps identify system-level weaknesses rather than pointing fingers at individuals. When employees report without fear, we get a more complete picture of the risks.

So, the aim is for employees to report as many errors as possible?

Exactly. The more incidents - even minor problems - are reported, the better major incidents can be prevented. This is because these reports create a better database for safety analyses. As a result, companies recognise risks earlier, find areas to learn from and can take active action.

What other opportunities does "Just Culture" offer?

For example, increased employee satisfaction. Data shows that staff turnover is 27 per cent lower in psychologically safe teams. With an open error culture, people are also more committed, less stressed, more cooperative and more willing to try out new skills. In addition, fewer mistakes are made overall because employees can learn not only from their own experiences, but also from the mistakes of others. The important thing is that you can report them at any time - without having to fear negative consequences or reprisals. As a military pilot myself, I learnt how important this is in an extreme situation.

What happened?

Despite the bad weather, we had the task of taking off with two F5E fighter jets for "supersonic air combat training" above the clouds. I was newly trained and flew as the "Son" - the second aircraft following the leader - with a very experienced fighter pilot. The exercise went smoothly at first, but the critical phase began on the return flight. Our fuel reserves were running low, so we had to return to the airfield quickly. My mission was clear: fly close to my superior and dive into the dense cloud cover together with him in a patrol flight - a challenging manoeuvre, especially under the given conditions. As soon as we plunged into the clouds, I was overcome by an uneasy feeling. I felt as if we were descending too early - but I had no way of checking this.

What have you done?

Despite my inexperience, I decided to express my uneasy feeling and bring it to the attention of the experienced supervisor. Without hesitation, he raised the nose of the aircraft slightly to look into my concerns. Seconds later, we burst through the clouds—only to find a massive rock face looming right in front of us. We both immediately lit the afterburners, pulled the aircraft upwards at full power and escaped disaster by a hair's breadth. This experience showed me how important it is that everyone - regardless of experience or hierarchy - can and should express their concerns openly and be taken seriously. I am still grateful today that I had the courage to express my uncertainty and that my experienced colleague reacted immediately. This event still characterises my conviction and my commitment to an open and safe error culture - and not just in aviation.

Based on such experiences, what do you recommend to companies in order to implement the "just culture" principle in practice?

Train all employees and establish low-barrier, anonymous channels for reporting safety concerns. In addition, companies should systematically analyse both mistakes and successes in team meetings, exchange information across hierarchical levels and hold regular briefing and feedback sessions.

What role do managers play in promoting this open error culture?

They play a crucial role in embedding a "just culture". This is why managers should set a good example, admit their own mistakes and openly address uncertainties - this is how they create an environment of trust. It is important that they combine this trust with clear expectations to promote a culture in which mistakes are seen as learning opportunities.

You spoke at Food Day 2025. What is the biggest challenge in implementing this principle in the food industry?

The balance between efficiency and safety. Like the aviation industry, there is constant pressure in the food industry to work faster and more cost-effectively. I therefore believe it is crucial to define clear "no-go" criteria that always prioritise safety over speed.

What else can make implementation more difficult?

High staff turnover. Just like the fear of sanctions. If employees fear negative consequences if they point out safety deficiencies, mistakes may be covered up. Without a safe environment for reporting, the concept of "Just Culture" therefore remains ineffective.

Aviation is highly regulated, as is the food industry. Does more regulation automatically mean more safety?

Not necessarily. Regulations create an important basis, but too many regulations can lead to a "do-it-by-the-book" mentality that stifles personal responsibility and critical thinking. I therefore differentiate between "compliance pilots", who strictly follow regulations, and "safety pilots", who understand their meaning and actively act. Companies need a similar approach: use regulations as a framework but promote a safety culture in which employees recognise and address risks independently.

Do we need additional standards such as ISO 9001:2015 in addition to the legal requirements?

Legal regulations define the minimum baseline. ISO 9001:2015, on the other hand, provides a framework for excellence in quality management. There are similar standards in aviation that go far beyond the legal requirements and help us to be proactive rather than reactive.

Can you elaborate on this? What are the advantages for a company that produces frozen pizza or pretzels, for example?

Firstly: systematic risk management. It helps to recognise and reduce risks at an early stage. Secondly, a process-orientated mindset. It optimises the entire production chain to ensure quality and efficiency. And thirdly: a framework for continuous improvement in which regular audits and analyses create a sustainable safety culture.

Let's take a brief look at the last point. How does ISO 9001:2015 support continuous improvement?

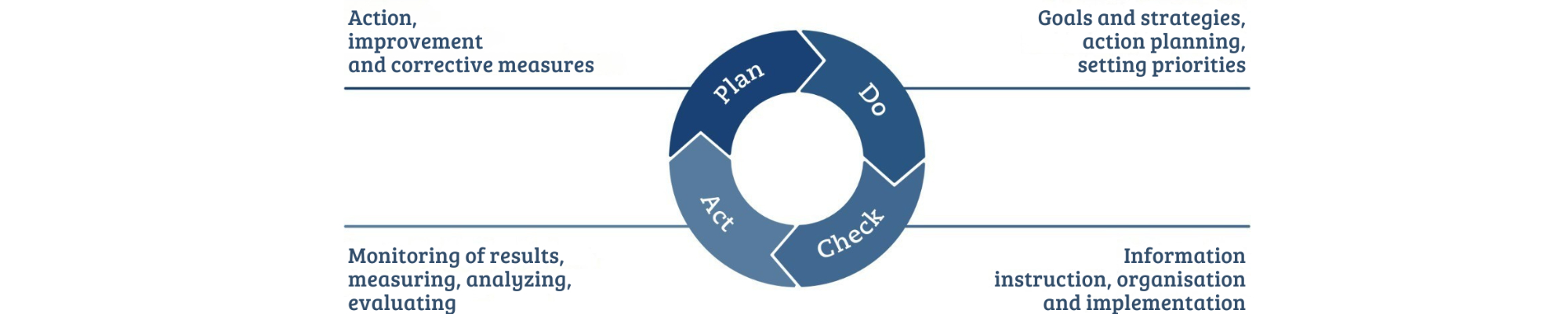

Through their PDCA cycle (see picture above), i.e. Plan-Do-Check-Act, which corresponds to our cockpit process: briefing, execution, debriefing, then reporting experiences and optimising processes. This cycle ensures that companies - as in aviation - systematically learn from experience and continuously improve.

Pilots regularly train for emergency situations. How important is such training in the food industry?

Extremely important. They not only prepare employees for rare crisis situations but also strengthen their ability to react correctly under pressure.

What are the decisive factors for effective emergency training?

Firstly: realism - scenarios are simulated under real time pressure and with realistic communication channels. Secondly, variability - different scenarios are practised to be prepared for different emergencies. And finally: constructive feedback, i.e. analysing what can be improved without apportioning blame. One of the biggest challenges isn’t expertise, it’s staying calm under pressure and making the right decisions. Studies also show that 70 per cent of errors occur at interfaces between teams - which is why training should be cross-departmental. Companies that invest in team training increase their operational resilience.